At The Table: Counter Archive & The Architecture of Control

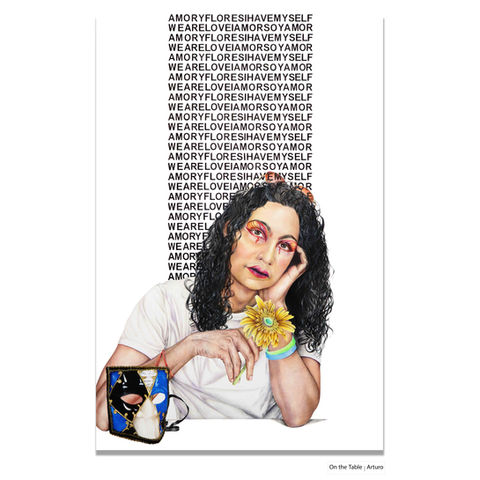

At the Table is an active research project that uses large-scale portraiture as a counter-archive. The work examines how queer lives are shaped, recorded and regulated through the intertwined systems of law, religion, medicine and bureaucracy. Rather than documenting identity, the drawings stage a confrontation with the structures that have historically positioned 2SLGBTQ+ people as peripheral—seen, but not recognised as full participants in the rooms where decisions about us are made.

The portraits take on the familiar visual grammar of grand state portraiture: a sitter at a white table, facing the viewer with clarity and steadiness. This is a deliberate misdirection. These tables echo places where power gathers—boardrooms, church basements, clinics, tribunals—but here the seat of authority is taken by those who were denied it. Each drawing becomes a site where the individual interrupts the institutional gaze.

Text appears across the portraits like residue left by systems of control. The words come from the sitters themselves: private, tender, furious, hopeful and unfiltered. They arrive as ledgers of lived experience, broken into fragments of self-authored testimony. The typography is bold and strict, echoing legal codes, medical documents and other forms used to police queer bodies and identities. The weight of the lettering creates a friction against the softness of the drawn face; it holds the viewer in place longer than a glance. These marks operate as evidence of the living architecture of control, showing how institutions write themselves onto bodies through documentation, categorisation and sanctioned narratives. The drawings carry that history and push back against it at the same time.v

Conceptual Framework for At the Table

1. Administrative Authority and the Seated Figure

The seated posture is drawn from historical portrait conventions in which the person with “the seat” held authority. At the Table repositions this structure. The sitter occupies a place typically tied to evaluation or judgment, but here they hold the position of witness, interrupting the visual hierarchy that once defined who was entitled to appear with authority.

2. Institutional Typography

The typographic system mirrors the fonts used in legal, medical, and bureaucratic documents. These styles signal regulation and standardization. Their presence on the portrait surface highlights how administrative systems have documented, classified, or restricted queer and trans people. The fonts act as institutional residue rather than decorative design.

3. White Clothing as Institutional Neutrality

White clothing removes cultural and economic markers, echoing the “neutral” or unmarked body in administrative imaging. In this context, white refers to the flattening effects of institutional processes, where individuality is stripped in favour of standardization. It signals structural erasure rather than purity or aesthetic minimalism.

4. Objects as Personal Evidence

The objects placed on the table serve as forms of personal evidence that fall outside institutional categories. Unlike historical portrait props used to communicate status, these items reflect memory, grounding, and lived experience. They function as components of testimony, countering the limited fields of information captured in formal records.

5. Hyperrealism as Counter-Documentation

Hyperrealism has historically been tied to authority—state portraiture, forensic illustration, and scientific observation. In this series, high-resolution drawing becomes a method of counter-documentation. It applies the visual precision of official imaging to individuals often misrepresented or excluded by those systems, creating records that operate outside institutional control.