Reclaiming History: Why I Borrow From the Language of Power

- jeannettesirois

- Jul 21, 2025

- 2 min read

Studio Conversations:

When I began At the Table (formerly On the Table), I kept circling this question: Who gets a seat? Historically, that seat—literal and symbolic—wasn’t offered to queer people. Portraiture, especially aristocratic and political, wasn’t neutral. It was a visual system of hierarchy. Every choice—pose, color, object—signaled rank and belonging. Those who didn’t fit were left out, erased from the cultural record.

So I started thinking: What happens if we take those codes and turn them on their head? That became the heart of At the Table.

The Seated Figure: Codes of Power

In historical portraiture, sitting wasn’t casual—it was a declaration of authority. A chair could function like a throne, saying: I command this space. My portraits echo that composure, but the meaning has shifted. Here, to take a seat isn’t to flaunt privilege; it’s to claim visibility in a space that once denied it.

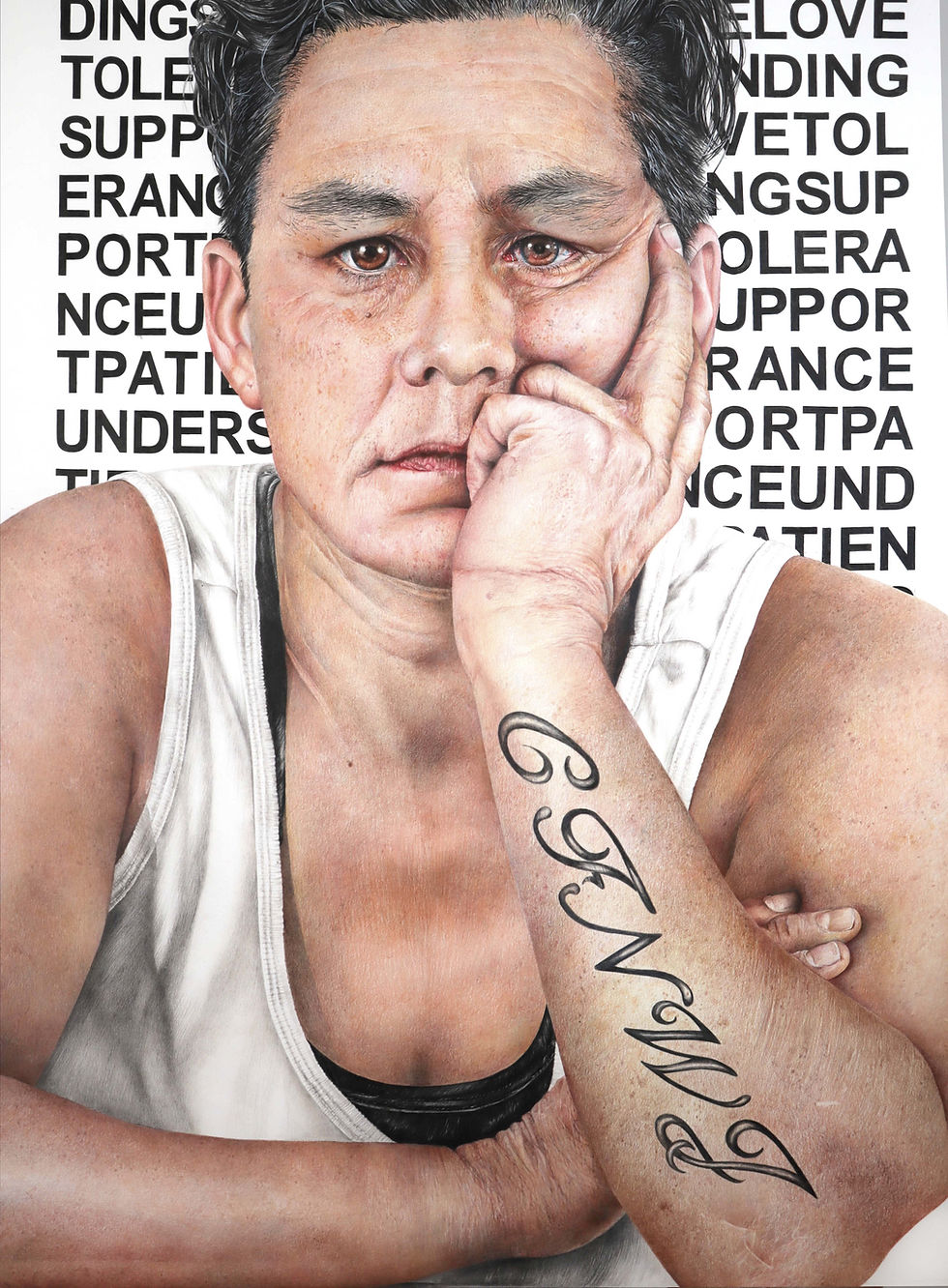

Typography: Bureaucratic Fonts as Resistance

You’ll notice block letters in the backgrounds—fonts pulled from bureaucratic language. These were designed for control: laws, forms, institutional decrees. Historically, they enforced compliance and erased individuality. They carried policies that criminalized queer lives. In this series, those same letters become something else: defiance. The fonts of silence now shout back.

The White Garments: Absence and Protest

In aristocratic portraiture, color meant wealth and status. White does the opposite. It strips away opulence, refusing the ornamental codes of privilege. White speaks to erasure—the blankness imposed by systems of control—but also to resilience. It becomes a radical simplicity: a queer aesthetic of refusal.

Objects: Ordinary Lives, Monumental Meaning

Classic portraits used props as status markers—globes, fine fabrics, religious books. In At the Table, objects are personal and unassuming: a hat, a keepsake, a fragment of memory. They’re not decorative. They hold narratives of love, endurance, and grief. They insist that ordinary lives matter as much as the elites once framed in oil and marble.

Hyperrealism: The Politics of Representation

Realism historically served power—immortalizing monarchs, clergy, and politicians. By applying the same precision to queer sitters, I grant them the permanence history denied. Hyperrealism here isn’t about showing off skill. It’s a refusal to let these lives be abstracted or erased. In a cultural moment thick with anti-queer rhetoric, this visibility is an act of courage—for the sitter and for the work.

At the Table exists in a time when books vanish from shelves, policies target queer bodies, and hate circulates as law. Against that tide, these portraits insist on presence. They claim the table. And they will not move.

Great article and it's good to see an explaination of the parts of your work.